Vermont’s first Education Fund was established in 1825 with money from the statewide wealth tax. The funds collected were distributed to the towns for the support of schools, and to pay for the new State Board of Education. The Fund has been in and out and up and down over the years, and remains with us as the source of support to our public schools. In recent years it has borne the brunt of much criticism and tinkering, and today stands at the center of the controversy surrounding the Governor’s education plan.

Sources of support

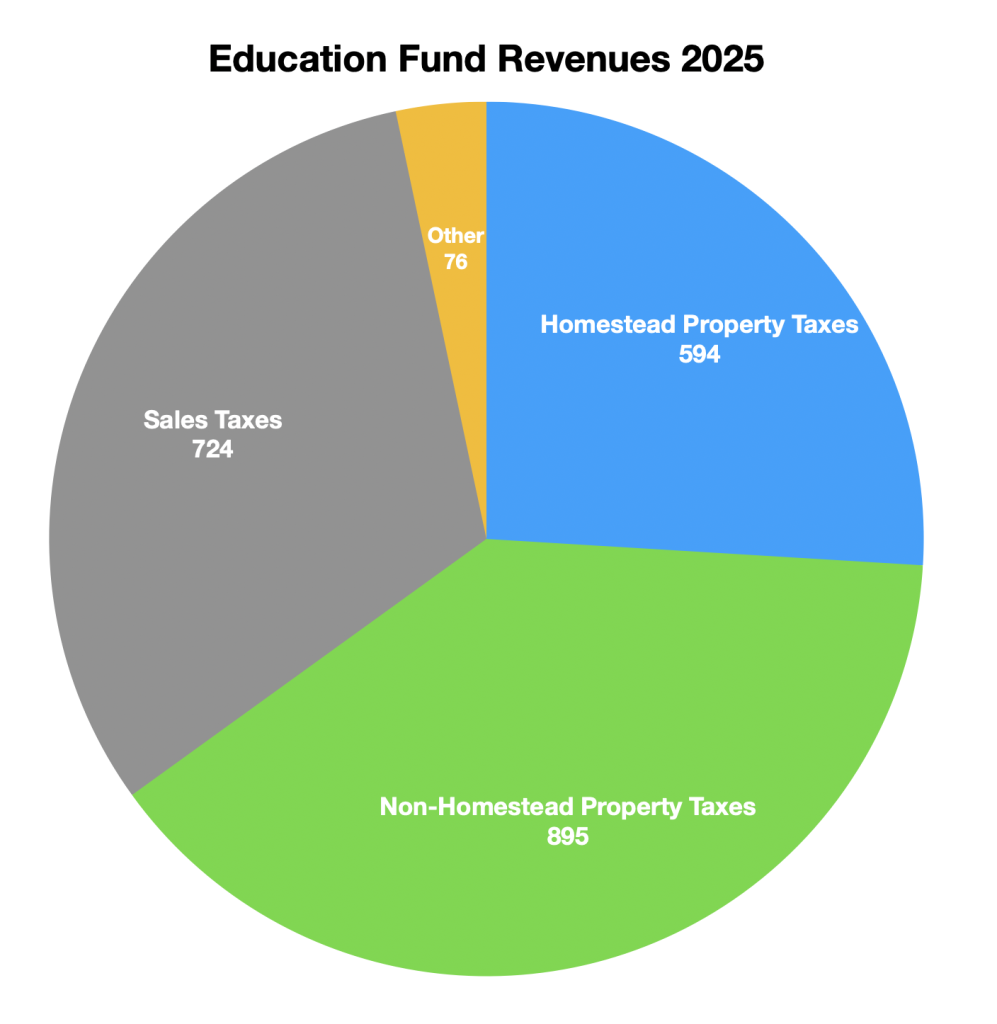

The Education Fund, which amounts to $2.3 billion in 2025, is fed by property taxes (65%), sales taxes (32%), and a few minor sources (3%). (The charts below show millions of dollars.)

Expenditures

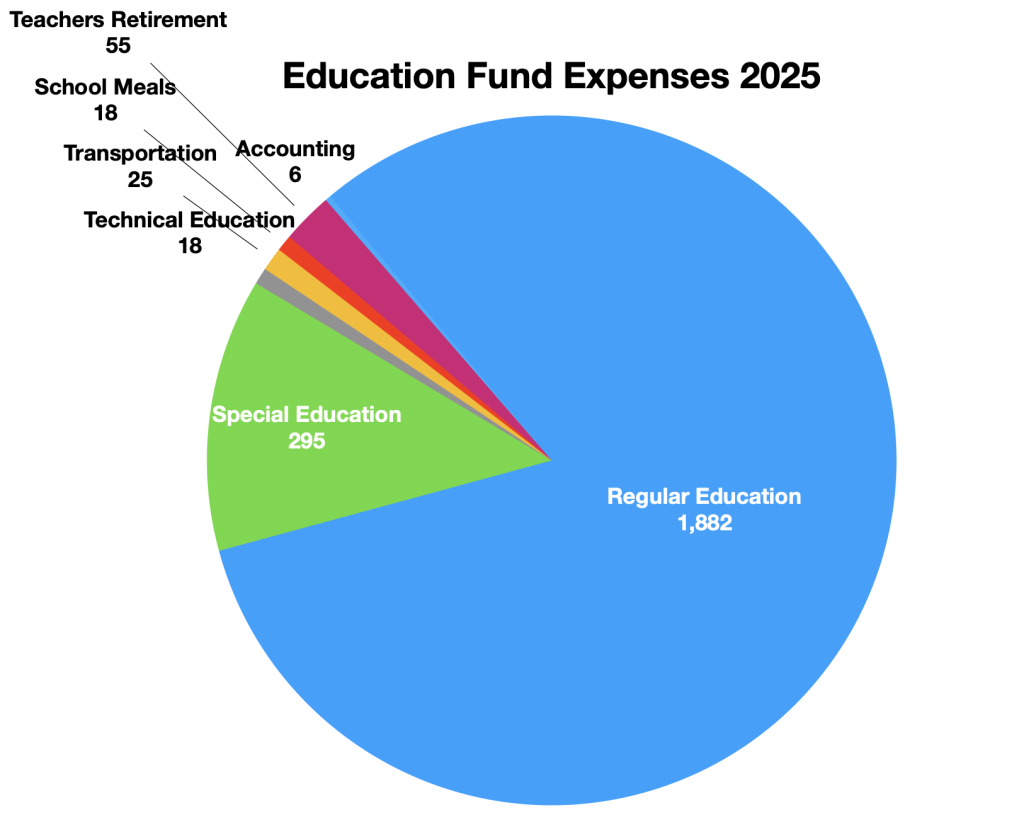

The Education Fund pays for PreK-12 regular, special, and technical education, as well as for school meals, school transportation, and teachers’ retirement.

Source: Education Fund Outlook for 2026

The amount that each school district gets from the fund depends on a complex and shifting variety of factors including how many students it educates, of what types, and how much it votes to spend. As such it is unpredictable; the amount the fund needs to collect from taxpayers is not known until voters act in the spring, well after the state budget has been drafted.

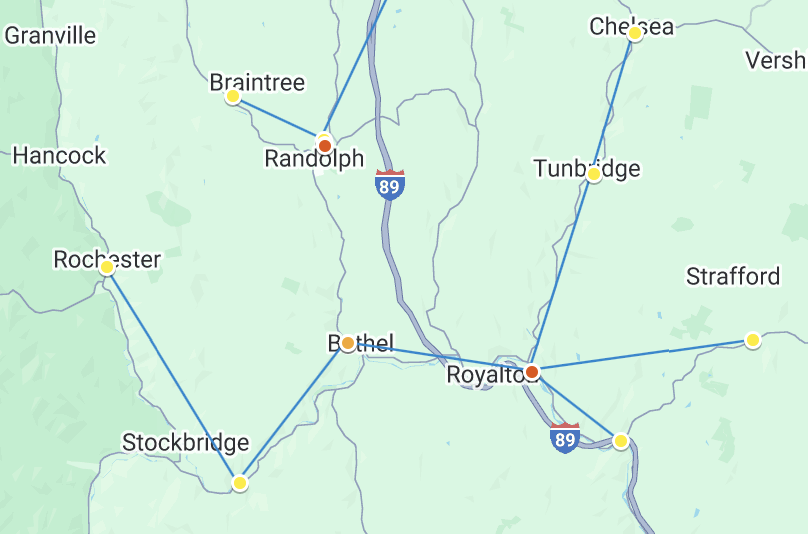

While the sales tax portion of the fund is collected by the state from hundreds of merchants, the property tax portion is paid to 251 town treasurers, who in effect send it to the state, which, after applying a complex formula that few understand, send it back out to 105 school districts and to low-income homeowners. This complexity has arisen in an attempt to equalize Vermont’s distribution of real property wealth, which ranges from $25 million per student in Stratton to $0.5 million in Fair Haven.

Vermont’s education fund today is hardly understandable, often unpredictable, seldom sufficient, and therefore unsustainable. We might do better if we simplify it, strengthen it, and insulate it from the political whims of the moment.

- First, let’s simplify it by letting the state collect the real property tax directly from owners, the same school tax rate no matter where you live.

- Second, let’s expand the definition of property to include the financial assets of wealthy citizens not currently taxed. See Vermont’s Wealth Tax: A Brief History, and WOOFs.

- Third, let’s allocate the money directly to the K-12 school districts based on the number of students, with slight adjustments for special circumstances. In this way, each student benefits from equal resources regardless of zip code.

Give this fund a year or two to build up a reserve, then move to a forward-funding model in which schools know a year in advance what their allocation will be, so they can build an expenditure budget accordingly. Along the way, set aside a school construction portion to support capital projects requested by the schools.

The per-student allocation would be set each year by the Legislature, based on the education price indexes compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The General Assembly would then set the statewide property tax rates. The latter would be adjusted annually to fulfill the needs of the former.

Such a fund would be easier to understand, easier to administer, more stable, and less subject to partisan politics. And thus sustainable.

Lower Property Tax

In addition, moving to a sustainable Education Fund would lower the property tax for most Vermonters. Currently, Vermonters own about $200 billion worth of wealth: $100 billion in real property that you can walk on, see, and touch; another $100 billion in financial assets, such as stocks and bonds, trust funds, and business equity. The former contributes to the education fund, the latter does not. To raise the $1.5 billion now sent to the Fund by property taxes, we could lower the tax rate to 0.75%, half of the current rate. See Education Fund Outlook, and Net Worth Held by Households

Leave a Reply