I have just finished reading the 154-page education reform bill as it emerged from the conference committee on Friday afternoon. In style, it combines the stream-of-consciousness of James Joyce with the non-sequiturs of Lewis Carroll. But not as much fun to read. It doesn’t do much to improve education. Instead it:

- sets up eight boards and commissions and task forces,

- sets minimum class sizes,

- proposes we reduce spending to $15,000 per student,

- calls for districts of 4000 to 8000 students each,

- expands the privileges of private schools,

- encourages over-identification of special ed students,

- spends over $4 million to administer its implementation.

Eight new boards and commissions

The bill creates a plethora of boards, commissions, task forces, advisory groups, working groups, and steering groups, with overlapping tasks.

Commission on the Future of Public Education in Vermont

“There is hereby created the Commission on the Future of Public Education in Vermont…The Commission shall cease to exist on December 31, 2025.” Now this commission already exists, yet it is re-created in this bill, reduced in scope, and given another six months to live. During its short lifetime, it was denied information and support from the Agency of Education, ignored by the Governor, and frustrated by the politicization of its mission. Why are we creating it again?

Commission Steering group

“On or before July 1, 2024, the Speaker of the House shall appoint two members of the Commission, the Committee on Committees shall appoint two members of the Commission, and the Governor shall appoint two members of the Commission to serve as members of a steering group.” The bill calls for something to happen in the past, for a commission that seems no longer serve any purpose. Why is this in the bill?

School District Redistricting Task Force

“There is created the School District Redistricting Task Force to recommend new school district boundaries and configurations to the General Assembly…On or before December 1, 2025, the Task Force shall submit a written report …The Task Force shall cease to exist on June 30, 2026.” How does this task force not duplicate the work of the Commission mentioned above? $120,000 is allocated to support their work.

School District Voting Ward Working Group

“There is created the School District Voting Ward Working Group to create voting district wards within the new school districts…The Task Force shall cease to exist on June 30, 2026.“ So how can we create voting wards within the new districts before we have defined the new districts? How many new entities will this add to our already bloated school governance system? $215,000 is allocated to support their work.

The State Board of Education

The bill re-establishes the already-existing State Board, with new membership and powers, and directs it to “initiate rulemaking to amend the Education Quality Standards.” Standards which do not exist at the moment. $200,000 is allocated for this re-establishment. And how is the work of the Board different from that of the Commission, the Steering Group, the Task Force, the Advisory Committees, the Agency, and the Working Group?

State Aid for School Construction Advisory Board

“There is hereby created the State Aid for School Construction Advisory Board, which shall advise the Agency on the implementation of the State Aid for School Construction Program.” School construction aid has not existed for 20 years, but it might be a good idea to allocate some funds for this purpose before setting up yet another board to administer it.

Education Fund Advisory Committee

“There is created the Education Fund Advisory Committee to monitor Vermont’s education financing system.” Already the legislative committees on Education, Ways and Means, and Finance; and the Agency of Education; and the Department of Taxes, are charged with this task. Perhaps adding another set of eyes will increase efficiency here.

Regional Assessment District Stakeholder Working Group

This has nothing to do with educational assessment, rather it’s a new set of agencies, one in each region, to coordinate listers’ property assessments across the state. It seems like they forgot to appropriate money for this new group.

It looks like we’re going to see lots of cooks in the Education Reform kitchen. Including one just to hold the stakes. What are the chances they’ll win a Michelin star?

Education quality

The bill mentions the importance of “Education Quality Standards” nine times, but the only specific standard listed is the minimum class size requirement grade by grade. Yet there is no research that suggests larger class sizes increase educational quality. In fact the opposite is true. Is the setting of class sizes best done by the legislature? This important policy has long been the prerogative of local school boards. I can find nothing else in the bill that would increase the quality of our schools.

Education funding

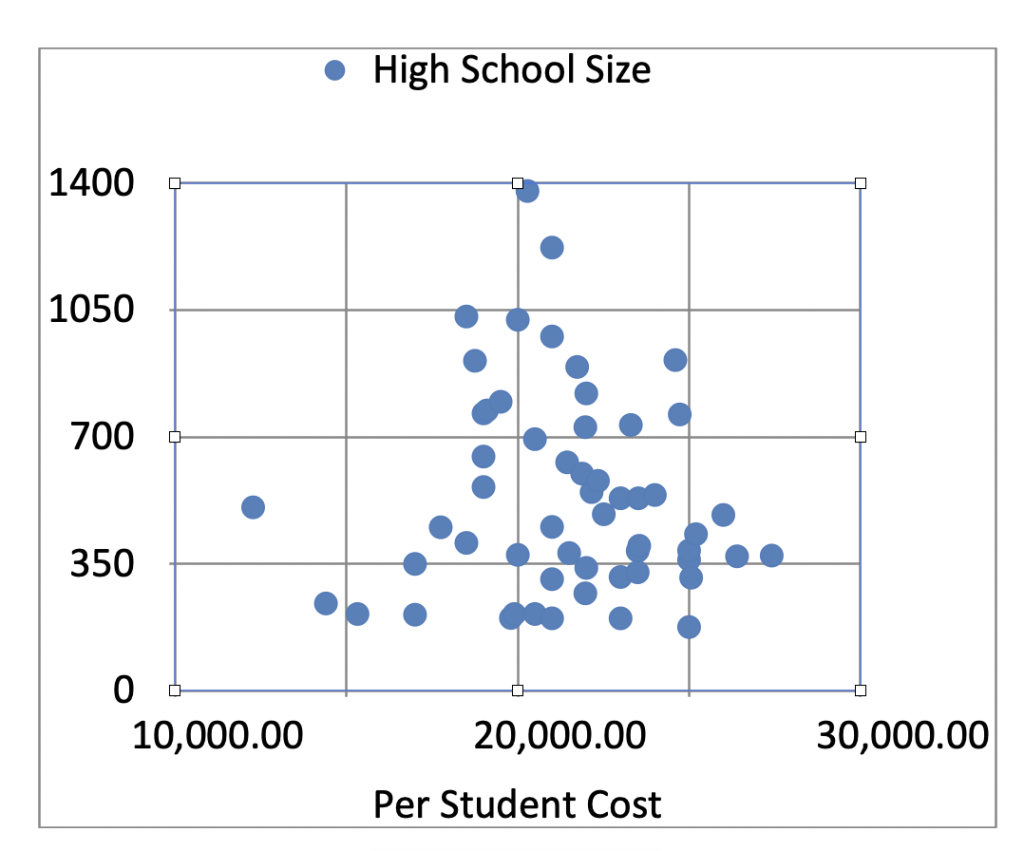

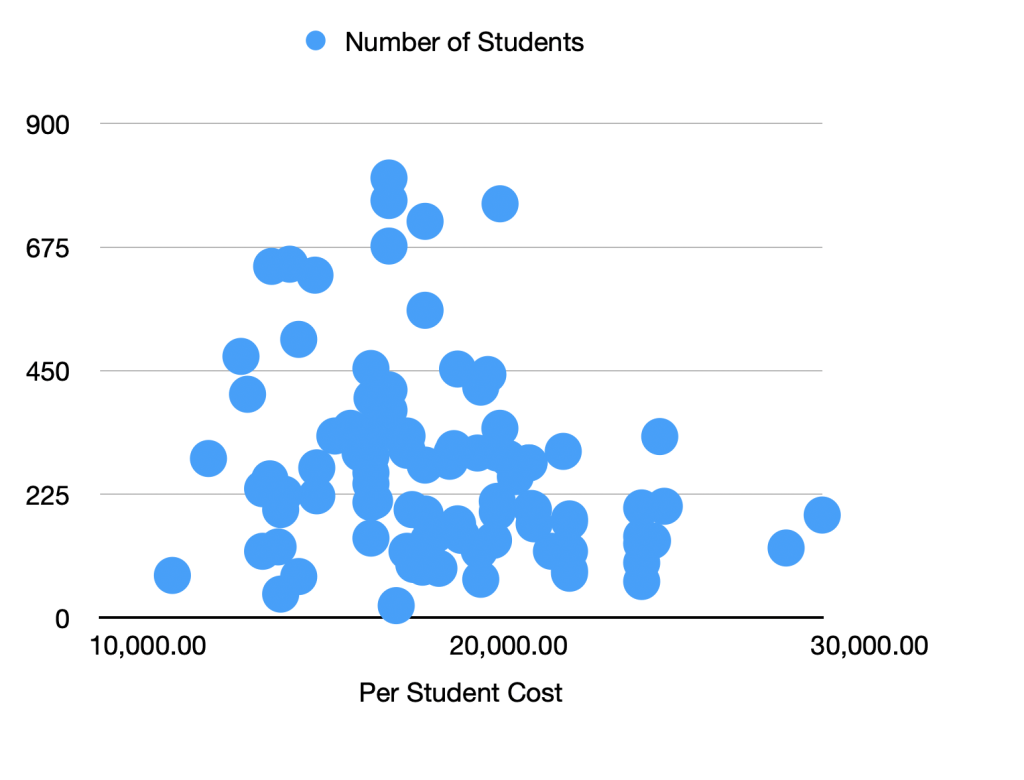

After a four-year phase in, the bill allows districts to spend up to $15,000 per student, but no more than that. For 99.9% of our students, this represents a considerable reduction from current levels. Today spending averages $20,000 per student. Only one district, Morgan, with 40 students, spends less than $15,000. The bill thus reduces public support for education by 25%. How can this approach improve educational quality? And for those of you interested in evidence-based legislation, know that spending is highly correlated with educational quality.

Large districts

The bill mandates districts of 4000 to 8000 students each. None of our districts in Vermont is this big. And the national research says that the highest quality (and lowest costs) are associated with districts of 2000 to 4000 students. A 5000-student district in the Northeast Kingdom, for instance, would stretch from Jay to Canaan to Lyndonville and take 3.5 hours to drive around. There is no evidence, nationally or in Vermont, that larger districts are less costly than smaller ones. To meet this mandate, every existing district in Vermont, even those that produce excellent results at reasonable costs, would need to be dismantled and rebuilt.

Private schools

Because the private school lobby spent lots of money at the State House this session, and because two of the six members of the Conference Committee work at private schools, the bill showers them with gifts. It’s bad enough that we currently send $60 million of taxpayer dollars each year in tuition payments to private schools, including religious schools, with no accountability; the reform bill would open the floodgates further. It would allow more taxpayer money to go to more private schools — just about any private school, anywhere, including, in the language of the bill:

- an approved independent school;

- an independent school meeting education quality standards;

- a tutorial program approved by the State Board;

- an approved education program;

- a public school located in another state;

- a therapeutic approved independent school located in Vermont or another state or country;

In addition, it would allow these schools a bonus of $750 per student over what’s provided to public schools. And two of the private schools — St. Johnsbury Academy and Burr & Burton — would be able to charge as much as they wanted in tuition. Which at current levels exceeds the state’s per-student allocation by $10,000. I wonder why these two private schools are singled out for special treatment? See The Academies. See Vermont Ethics Code, section 1203 on conflicts of interest.

Why are we doing this? How does this strengthen our public schools?

Special education

While the bill calls for the development of a strategic plan to overhaul special education — the second largest driver of increased costs — it at the same time incentivizes the over-identification of students. It calls for each student in special ed Category C to get $37,350 per year, and expands the category to include not only blind and deaf students but also anyone on the “autism spectrum.” This offers a clear financial incentive for a district to include as many students as possible in this category. And since the diagnosis of autism is fraught with inconsistencies, we have seen a tripling of identifications in the last decade. In some Vermont districts, almost a third of the students are so identified, far above the national averages. Lead us not into temptation.

Administrative costs

The bill proposes a six-year timeline for its implementation, and in the first year calls for an appropriation of over $4 million to pay for the administrative costs of the various boards, commissions, advisory groups, consultants, studies, and clerks.( But no money for school improvement.) Here is the list of expenditures:

- Adds $2.8 million to AOE budget for 2026 for administrative expenses. Five new positions.

- Spends $150,000 for a strategic plan for special ed.

- Spends $400,000 for consultants to determine the per-student payment.

- Spends $150,000 for a study of the income sensitivity of the property tax.

- Spends $200,000 to update the State Board’s rules.

- Spends $170,000 to support the Redistricting Task Force.

Taxation

The bill further complicates the already unpredictable statewide and local property tax system by adding new categories to the homestead exemption and income sensitivity. Why are we setting forth a tax system before we know where the districts will be? And the bill does nothing to expand the tax base so as to focus on ability to pay.

Conclusion

This bill will reduce educational quality in Vermont by cutting spending by 25%, adding more task forces and boards to an already confused governance model, increasing class size, and creating large districts that don’t fit Vermont’s communities. It’s also very difficult to read. And expensive.